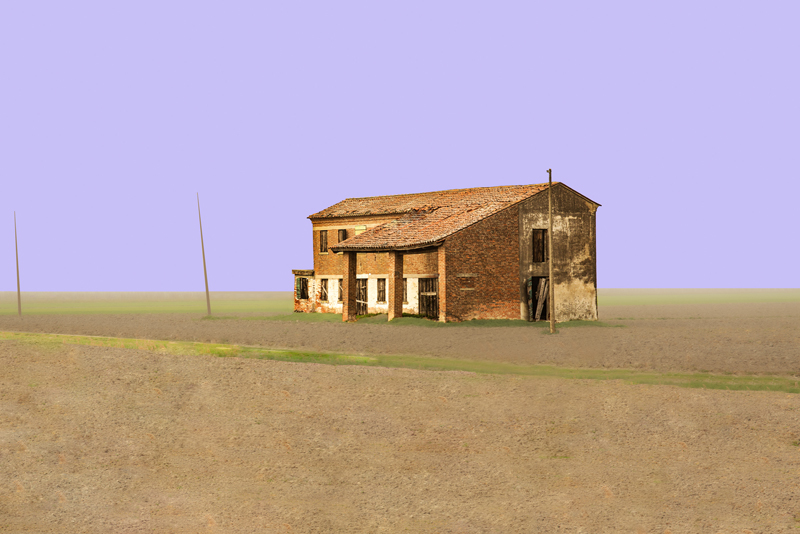

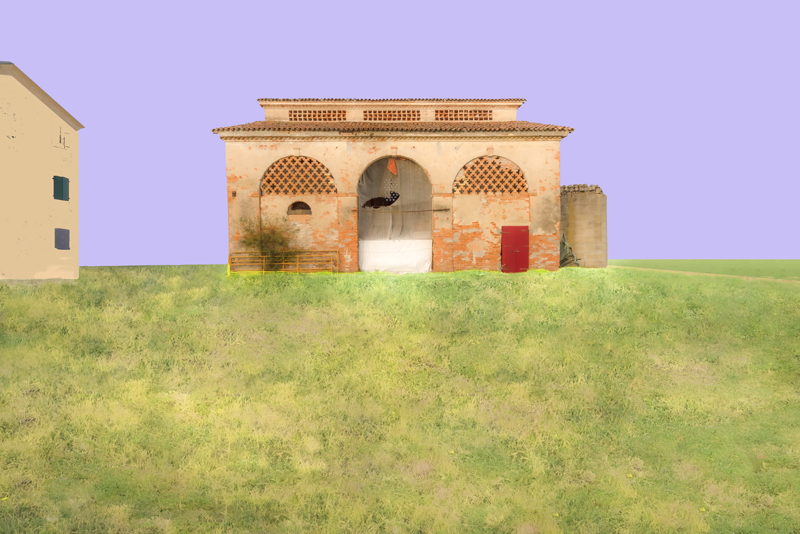

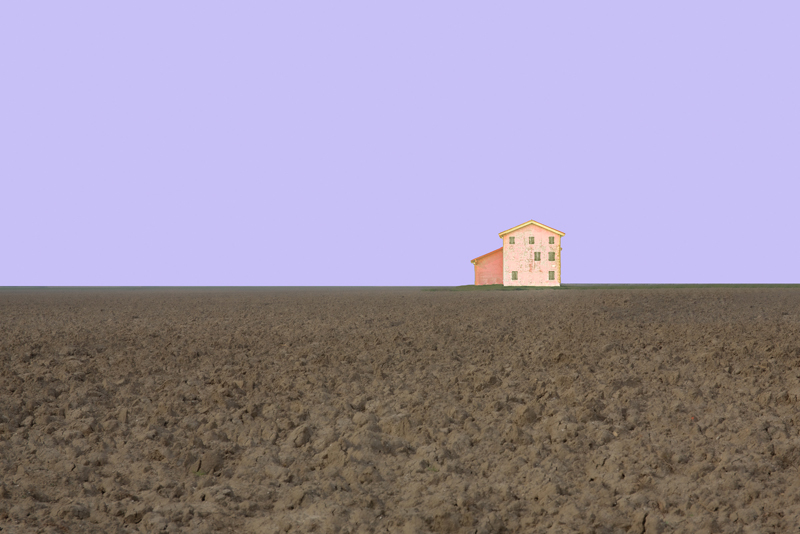

Questo lavoro nasce dal mio personale desiderio di approfondire il rapporto emotivo-affettivo che mi lega da tempo al paesaggio del Veneto Orientale, più specificatamente quello del basso Piave, caratterizzato, fra l’altro, dalla presenza di un particolare tipo di architettura, quello delle cosiddette case coloniche, che ne costituiscono parte fondamentale ed integrante.

La loro presenza, ad un osservatore attento, non passa inosservata, purchè si scelga di percorrere le provinciali a bassa velocità o, meglio ancora, quando ci si inoltri nella viabilità secondaria.

E’ stato necessario spendere una certa quantità di tempo ed eseguire un’attenta ricerca sulle mappe prima di trasferirsi sul campo per poter poi, una volta sul posto, approcciare il soggetto con la giusta prospettiva e nelle adeguate condizioni di luce, nonché disponendo dell’attrezzatura fotografica più idonea.

Altrettanto indispensabile è stato svolgere preventivamente una serie di approfondimenti del contesto storico geografico del tema in questione.

Da queste premesse appare chiaro come l’intento finale non fosse quindi quello di organizzare poi il materiale che avrei acquisito con un fine documentale, operazione che l’abbondanza del materiale fotografico raccolto avrebbe anche potuto consentire, ma di trarre da esso quegli spunti emozionali, che erano lo scopo principale che mi aveva spinto ad intraprendere questo viaggio.

Il contesto storico-geografico

Le progressive bonifiche di questi territori, attuate via via con maggiore intensità ed efficacia nell’ultimo ventennio del XIX secolo e poi nella prima metà del XX secolo, crearono la possibilità di ampliare notevolmente le aree destinate all’agricoltura.

I Consorzi di Bonifica qui sorti, così come accaduto in altre zone del Veneto e d’Italia, ne sono un’evidente testimonianza.

La casa colonica, che si diffuse come modello costruttivo in queste zone prevalentemente fra il 1880 e il 1935, aveva la funzione di fornire un’abitazione adiacente al posto di lavoro ai braccianti che lavoravano la terra con i contratti di mezzadria. Queste strutture sorgevano generalmente abbastanza isolate in ciascuna delle numerose proprietà terriere. Tuttavia già verso la fine degli anni ’50 del ‘900 il processo di industrializzazione, lo sviluppo turistico verso il mare e la meccanizzazione delle lavorazioni agricole ridussero progressivamente il numero di braccianti necessari alle attività agricole. Nel 1964 venne definitivamente abolita in Italia la mezzadria. L’alluvione del 1966 inoltre dimostrò che il fiume non era ancora del tutto sotto controllo.

Tutto ciò determinò, in tempi piuttosto rapidi, cambiamenti profondi a livello sociale e lavorativo con forte spinta all’inurbamento di una quota importante della popolazione. Pertanto queste grandi strutture vennero, da un giorno all’altro si potrebbe dire, abbandonate ed ora rimangono solo come testimonianze importanti di una precisa fase storica: la loro demolizione avrebbe un costo elevato e purtroppo quindi il loro destino, in assenza di, al momento non previsti interventi conservativi, sembra essere il lento degrado.

Ringrazio il dr. Piergiorgio Rossetto, profondo conoscitore di questi territori e delle loro caratteristiche antropologiche, per la preziosa consulenza che ha generosamente messo a mia disposizione.

Sono andati

Lo sguardo di un viaggiatore, che volesse calarsi nella suggestiva atmosfera del basso Piave, verrebbe dopo non molti kilometri catturato dalla presenza discreta, nel paesaggio, di insoliti imponenti edifici integrati con inattesa materica naturalezza nelle campagne.

Si tratta delle cosiddette case coloniche. Ciò finisce per creare nella sua mente, via via che in questi luoghi va inoltrandosi, giorno dopo giorno, una sorta di sensazione di appuntamento atteso.

Ho vissuto questa esperienza in modo emotivamente intenso, che esulava da intenti documentali.

Quel che ho cercato di raccontare, “illustrando” ed inserendo quindi una forte componente interpretativa, è una storia, una delle tante storie nascoste in queste zone di confine fra terra e acqua. Da osservatore stupito e curioso, quale io mi sono sentito in tutto questo lento percorso di scoperta, ho tentato di restituire nuova vita a questo paesaggio apparentemente “dimenticato”, utilizzando a volte anche la mia immaginazione, ma provando più spesso a coglierne la ritrosa poeticità, che ho voluto tentare di far emergere. Vite passate s’intuiscono all’interno ed intorno a questi monumenti di una realtà contadina, ormai estinta. Dinosauri di pietra marcano il territorio, quasi un monito a non scordare chi qui ha gioito, sofferto e lavorato duramente e operosamente. Ho realizzato quindi immagini che si potrebbero definire vivaci, in cui tuttavia la patina del tempo mantiene una sua discreta inconfondibile presenza.

Nel marzo 2024 è stato Silver Winner in Fine Art Architecture ai MUSE Photography Award

Nel gennaio 2024 è stato Gold Winner in Fine Art Landscape ai Tokyo International Photo Awards.

Questo lavoro nel 2023 è stato Silver Winner al New York Photography Awards

Questo lavoro è stato pubblicato in maggio 2023 su l’Oeil de la Photographie

They Have Gone

This work stems from my personal desire to explore the emotional-affective relationship that has long linked me to the landscape of Eastern Veneto, more specifically that of the lower Piave, characterized, among other things, by the presence of a particular type of architecture, that of the so-called farmhouses, which form a fundamental and integral part.

Their presence, to an attentive observer, does not go unnoticed, as long as you choose to travel along the provincial roads at low speed or, better still, when you enter the secondary road network.

It was necessary to spend a certain amount of time and carry out careful research on the maps before moving to the field in order to then, once on site, approach the subject with the right perspective and in the right light conditions, as well as having the suitable photographic equipment.

Equally essential was to carry out in advance a series of in-depth analyzes of the historical and geographical context of the topic in question.

From these premises it is clear that the final intent was therefore not to then organize the material that I would have acquired with a documentary purpose, an operation that the abundance of photographic material collected could also have allowed, but to draw from it those emotional cues, which were the main purpose that had prompted me to embark on this journey.

The historical-geographical context

The progressive reclamation of these territories, implemented gradually with greater intensity and effectiveness in the last twenty years of the 19th century and then in the first half of the 20th century, created the possibility of considerably expanding the areas destined for agriculture.

The Reclamation Consortiums that have arisen here, as happened in other areas of the Veneto and Italy, are clear evidence of this.

The farmhouse, which spread as a constructive model in these areas mainly between 1880 and 1935, had the function of providing a house adjacent to the workplace for the laborers who worked the land with sharecropping contracts. These structures generally arose quite isolated in each of the numerous landholdings. However, already towards the end of the 1950s, the industrialization process, the tourist development towards the sea and the mechanization of agricultural processes progressively reduced the number of laborers needed for agricultural activities. In 1964, sharecropping was definitively abolished in Italy. The 1966 flood also demonstrated that the river was not yet fully under control.

All this determined, in a rather rapid time, profound changes at a social and working level with a strong push towards the urbanization of an important part of the population.

Therefore these large structures were, one could say overnight, abandoned and now remain only as important evidence of a precise historical phase: their demolition would have a high cost and unfortunately therefore their fate, in the absence of, at the moment no conservative interventions are foreseen, it seems to be the slow degradation.

I thank Dr. Piergiorgio Rossetto, a profound connoisseur of these territories and their anthropological characteristics, for the precious advice that he has generously placed at my disposal.

The gaze of a traveller, who would like to immerse himself in the evocative atmosphere of the lower Piave, would be captured after a few kilometers by the discreet presence, in the landscape, of unusual imposing buildings integrated with unexpected material naturalness in the countryside.

These are the so-called farmhouses. This ends up creating in his mind, as he progresses through these places, day after day, a sort of sensation of an awaited appointment.

I lived this experience in an emotionally intense way, which went beyond documentary intent.

What I have tried to tell, “illustrating” and therefore inserting a strong interpretative component, is a story, one of the many stories hidden in these border areas between land and water. As an astonished and curious observer, as I felt throughout this slow journey of discovery, I have tried to give new life to this apparently “forgotten” landscape, sometimes also using my imagination, but more often trying to grasp its coy poetry , which I wanted to try to bring out. Past lives can be guessed inside and around these monuments of a peasant reality, now extinct. Stone dinosaurs mark the territory, almost a warning not to forget those who have rejoiced, suffered and worked hard and industriously here. I therefore created images that could be defined as lively, in which however the patina of time maintains its discreet, unmistakable presence.

In March 2024 this work was Silver Winner at Fine Art Architecture in MUSE Photography Award

This work in January 2024 was Gold Winner at Tokyio International Photo Awards in Fine Art Landscape

This work in 2023 was Silver Winner at New York Photography Awards

This work was published in May 2023 in l‘Oeil de la Photographie