In quel precipizio è Matera

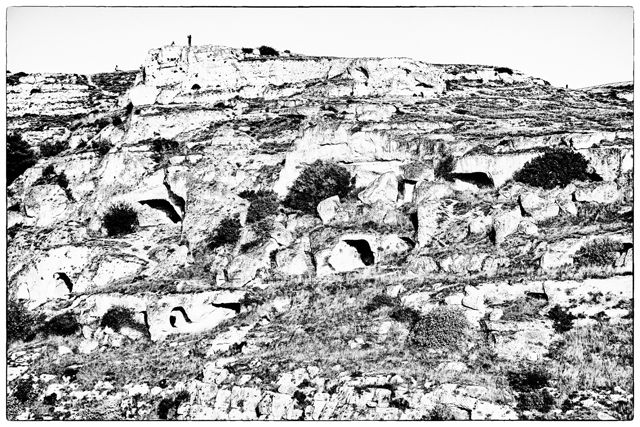

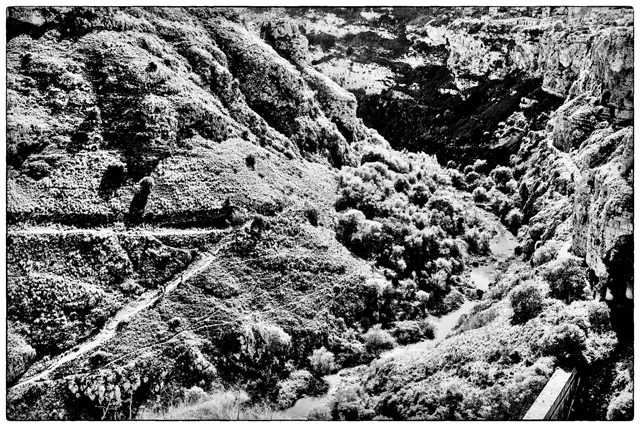

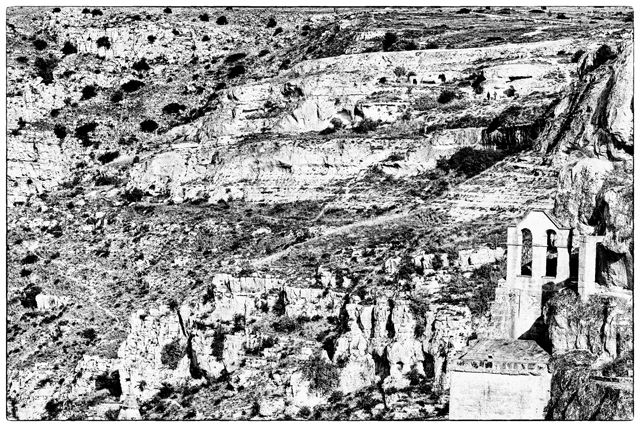

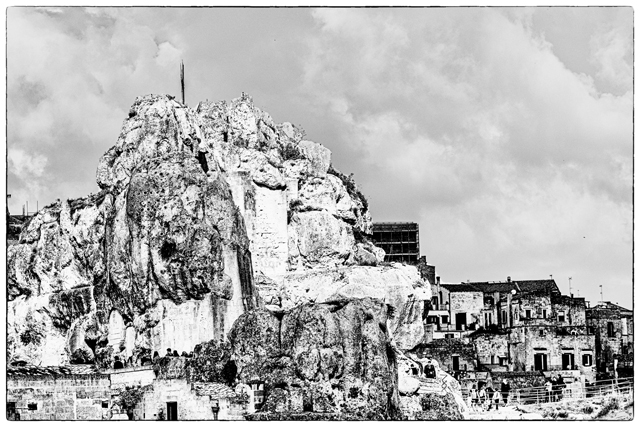

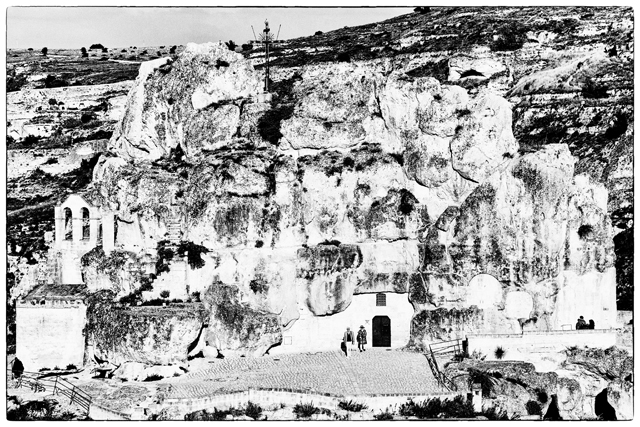

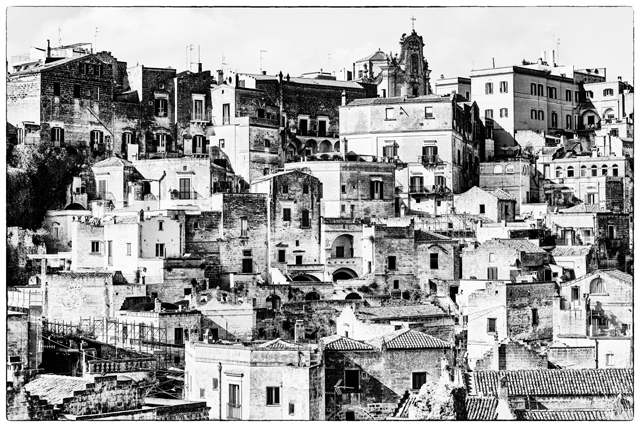

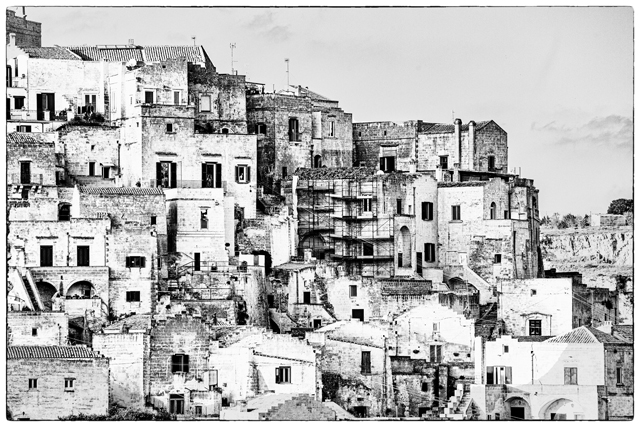

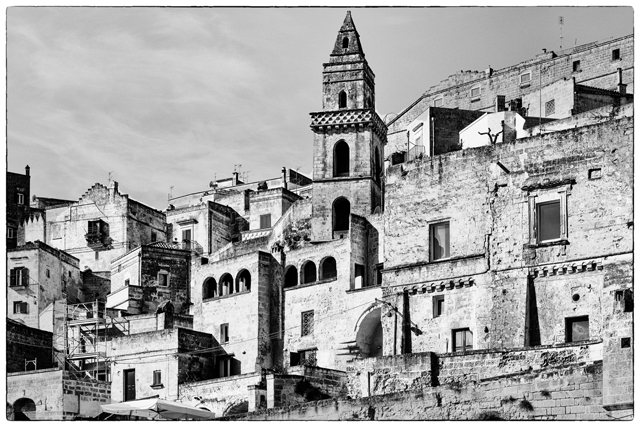

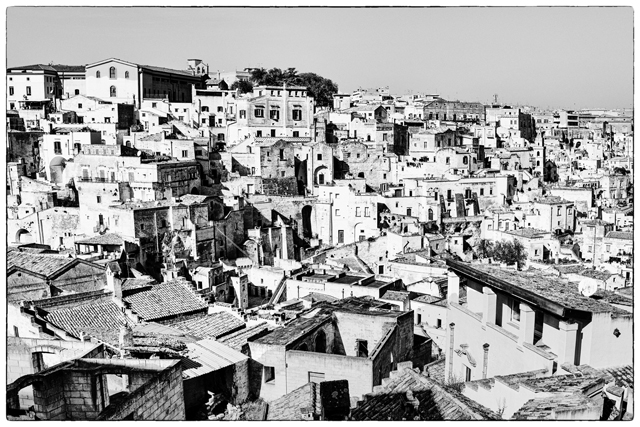

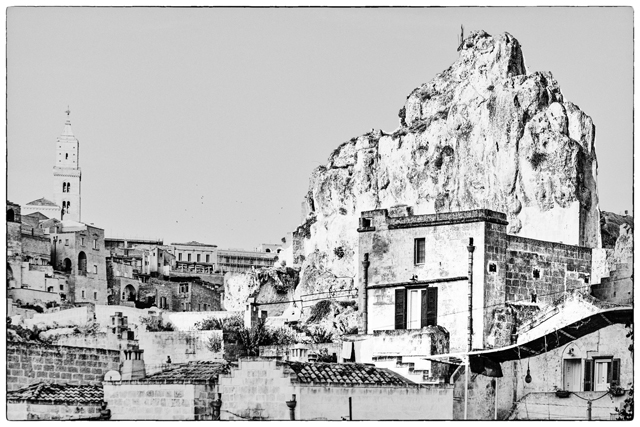

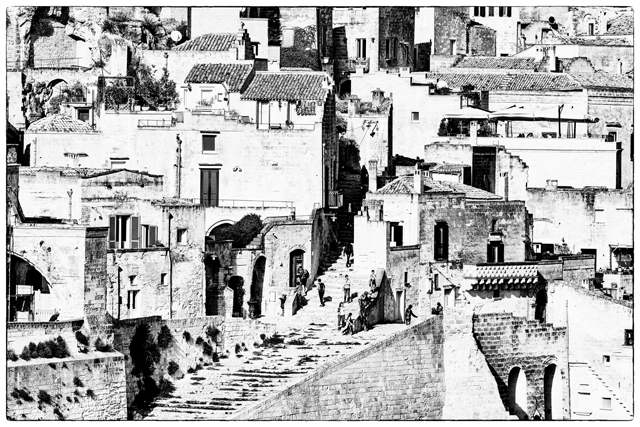

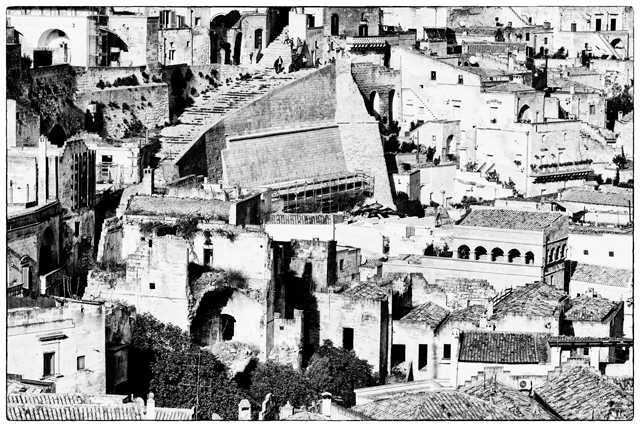

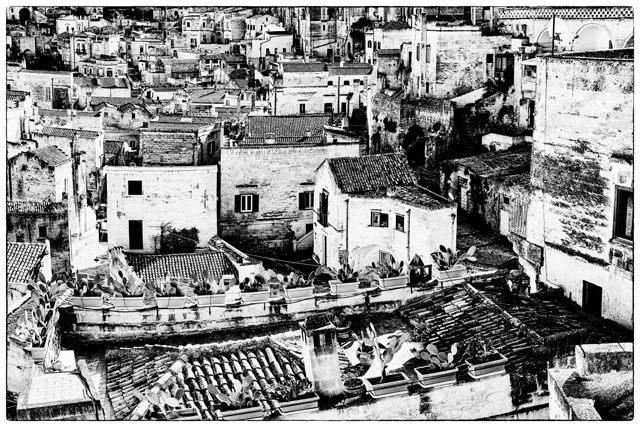

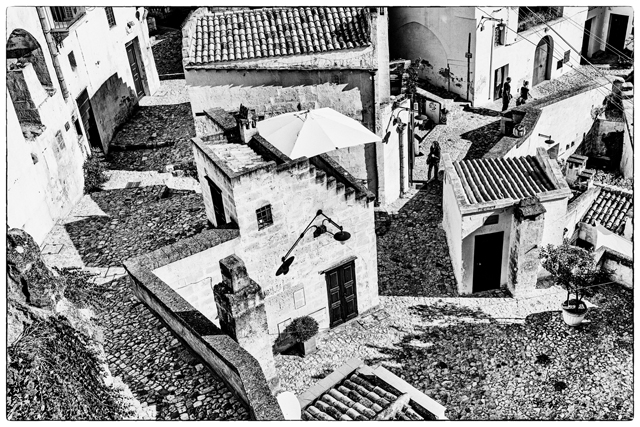

“Arrivai ad una strada che da un solo lato era fiancheggiata da vecchie case e dall’altro costeggiava un precipizio. In quel precipizio è Matera. Di faccia c’era un monte pelato e brullo, di un brutto color grigiastro, senza segno di coltivazioni né un solo albero: soltanto terra e pietre battute dal sole. In fondo un torrentaccio, la Gravina, con poca acqua sporca ed impaludata tra i sassi del greto. La forma di quel burrone era strana: come quella di due mezzi imbuti affiancati, separati da un piccolo sperone e riuniti in basso da un apice comune, dove si vedeva, di lassù, una chiesa bianca: S.Maria de Idris, che pareva ficcata nella terra. Questi coni rovesciati, questi imbuti si chiamano Sassi, Sasso Caveoso e Sasso Barisano.” (Carlo Levi, Cristo si è fermato ad Eboli)

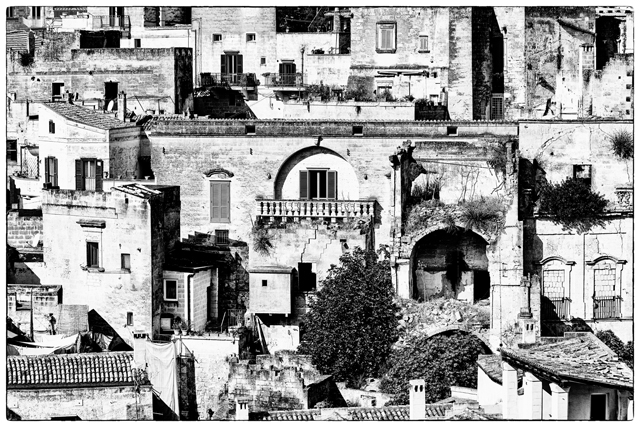

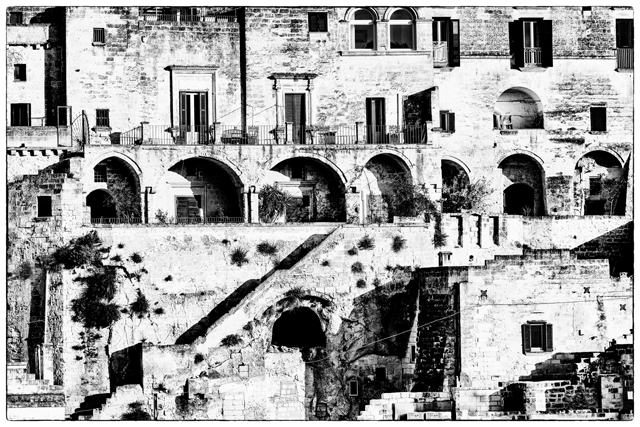

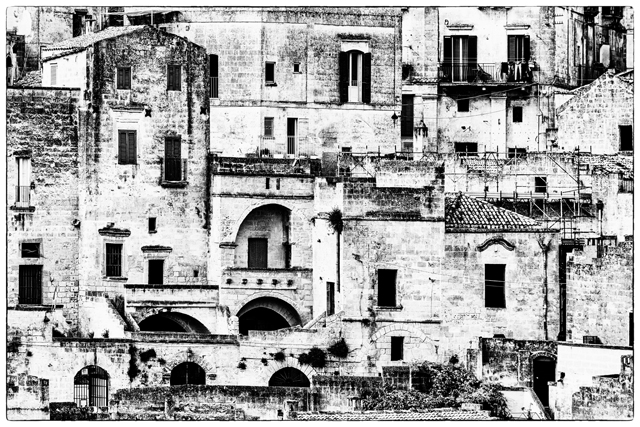

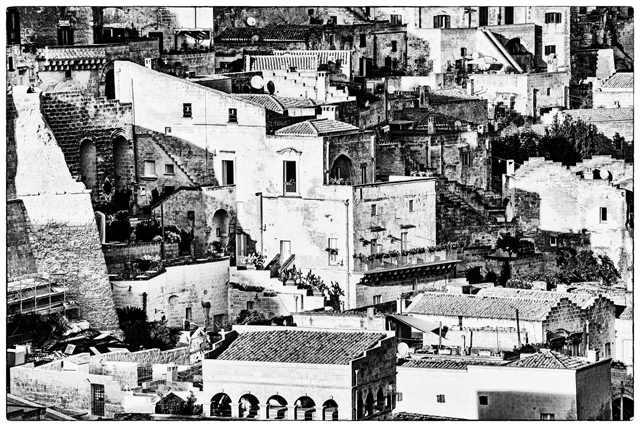

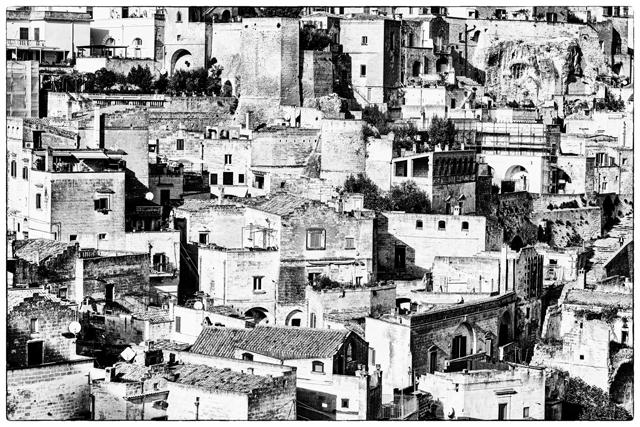

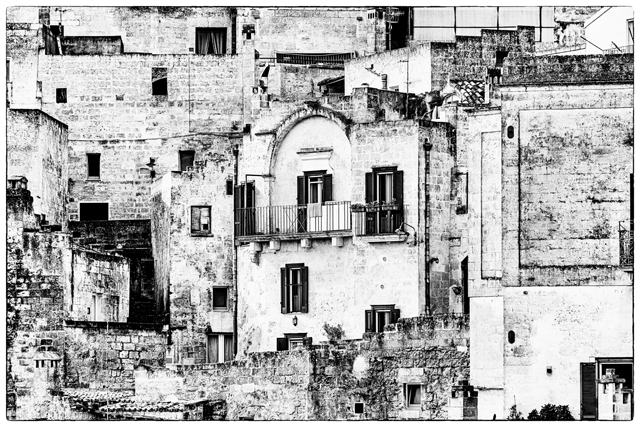

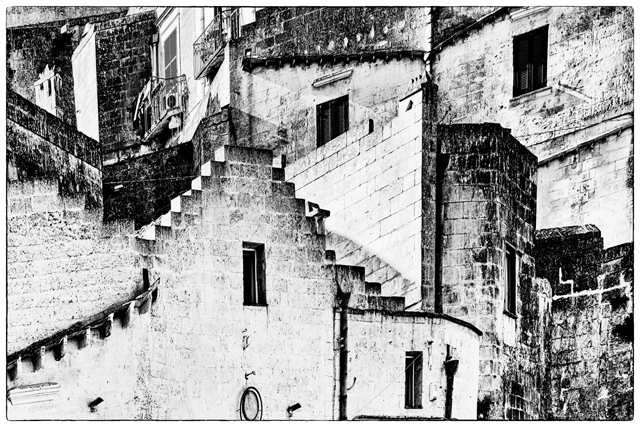

Descrizione epocale ed indelebile quella fornita dal grande letterato e pittore, che compone un quadro realistico ed al tempo stesso ideale: un triangolo che pone il suo vertice inferiore nella Gravina e si sviluppa dal fondo alla superficie costituendo la natura e la città stessa dei sassi. Insieme esse rivestono le pendici del “burrone” in un inestricabile struttura interconnessa e profondamente aggrappata alla terra. In ogni direzione emergono dalla roccia tufacea strutture con un ordine solo apparentemente casuale, dettato in realtà da un antico sapere. L’orientamento di tetti e facciate, la disposizione di ogni apertura, nulla è lasciato al caso. Di fronte a novemila anni ininterrotti di storia rimaniamo attoniti. Scrutiamo, abbacinati, questa primitiva complessità, tentando di comprenderne a fondo tutti gli aspetti. La geniale creazione di una sorta di microclima ideale e la gestione oculata delle acque ne costituiscono gli aspetti fondamentali. Ciò ha creato una bellezza inedita, una poetica della concretezza creata dagli uomini per gli uomini.

In the gully lay Matera

I found a street with a row of houses on one side and on the other a deep gully. In the gully lay Matera. From where I was, higher up, it could hardly be seen because the drop was so sheer. All I could distinguish as I looked down were alleys and terraces, which concealed the houses from view. Straight across from me there was a barren hill of an ugly gray color, without a single tree or sign of cultivation upon it, nothing but sun-baked earth and stones. At the bottom of the gully a sickly, swampy stream, the Bradano, trickled among the rocks. The hill and the stream had a gloomy, evil appearance that caught at my heart. The gully had a strange shape: it was formed by two half-funnels, side by side, separated by a narrow spur and meeting at the bottom, where I could see a white church, Santa Maria de Idris, which looked half-sunk in the ground. The two funnels, I learned, were called Sasso Caveoso and Sasso Barisano. (Carlo Levi, Christ stopped at Eboli, translation by Frances Frenaye)

An epochal and indelible description provided by the great writer and painter, who composes a realistic and at the same time ideal picture: a triangle that places its lower vertex in the Gravina and develops from the bottom to the surface constituting nature and the city itself of stones. Together they cover the slopes of the “ravine” in an inextricable, interconnected structure deeply attached to the earth. In every direction, structures emerge from the tufaceous rock with an apparently random order, actually dictated by ancient knowledge. The orientation of roofs and facades, the arrangement of each opening, nothing is left to chance. Facing with nine thousand uninterrupted years of history, we are astonished. We scrutinize, dazzled, this primitive complexity, trying to fully understand all its aspects. The ingenious creation of a sort of ideal microclimate and the careful management of the water are its fundamental aspects. This has created an unprecedented beauty, a poetics of concreteness created by men for men.